Measuring angles within arbitrary metric spaces

First published October 02, 2020Tags: [

maths

metric-geometry ]

We will generalise the concept of angles in Euclidean space to any arbitrary metric space, via Alexandrov (upper) angles.

A familiarity with metric spaces shall be assumed for obvious reasons, as well as a passing familiarity with inner product spaces.

1. Introduction and Preliminaries

Before we can generalise we must agree on a definition: what is an angle? Wikipedia gives the following answer to this question.

In plane geometry, an ‘angle’ is the figure formed by two rays, called the sides of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the vertex of the angle. […] ‘Angle’ is also used to designate the measure of an angle or of a rotation.

Defining an angle as a figure will not lead to any interesting mathematics, so for the purposes of this post we shall identify an angle with its size. More formally, we will think of an (interior) angle in the Euclidean plane \(\mathbb R^2\) as a function \(\angle\) mapping two straight lines which share an endpoint to a real number \(\alpha \in [0,\pi]\). Clearly then, if we wish to generalise this idea of “angles” to a generic metric space, we must first generalise what we mean by a “straight line”. In metric geometry, we typically achieve this by define a “straight line” as an isometric embedding of some closed interval. This embedding is known as a geodesic, and is defined precisely as follows.

Definition 1.1. (Geodesics) Let \((X,d)\) be a metric space. A map \(\varphi : [a,b] \to X\) is called a geodesic if it is an isometric embedding, i.e. if for all \(x,y \in [a,b]\), we have

\[d(\varphi(x), \varphi(y)) = | x - y |.\]We say \(\varphi\) issues from \(\varphi(a)\). We say that \(\varphi\) connects \(\varphi(a)\) and \(\varphi(b)\), and a space where any two points may be connected by a geodesic is a geodesic space. If this geodesic is always unique (i.e. precisely one geodesic connects any two points in a space), the space is said to be uniquely geodesic.

We similarly we refer to an isometric embedding \(\psi : [c,\infty) \to X\) as a geodesic ray. The image of a geodesic or geodesic ray is called a geodesic segment. We may sometimes denote a geodesic segment between two points \(x\) and \(y\) in space by \([a,b]\).

Our goal here is to generalise the Euclidean definition of an angle between two geodesics, typically defined using the classical law of cosines such that it may be applied to an arbitrary metric space. This will take the form of a function \(\angle\) which will take as input two geodesics (or geodesic rays) issuing from the same point and output a real number in the required range.

Remark. At this point, we may note that an arbitrary metric space need not contain any geodesic segments. One may now be tempted to point out that the title of this post is thus an exaggeration and the upcoming definition cannot possibly apply to all metric spaces. I would retort however that for a metric space \(X\), the statement “we can measure the angle between any two geodesics in \(X\) with a shared endpoint” holds even in the case that no such geodesics exist in \(X\), for the same reason that “every element of the empty set is puce-coloured” holds.

Before we get to our key definitions, some notational and terminological remarks. The Euclidean norm will be denoted by \(\| \cdot \|_2\). Secondly, when we refer to a vector space within this post, we will be speaking specifically about real vector spaces - i.e. vector spaces over the field \(\mathbb R\).

2. Definitions

The overall idea of this generalisation will be to choose a point on each geodesic, and consider the triangle formed by these points and the initial point. We then observe the behaviour of this triangle as these points move arbitrarily close to the initial point, and in taking the limit we will hopefully find our generalisation. Of course to make any sense of the “triangle” formed in our metric space between any three points, we need some way to make a direct comparison to a similar Euclidean shape. This is where the idea of a comparison triangle comes in, and indeed we have our first definition.

Definition 2.1. (Comparison triangles) Let \(X\) be a metric space, and let \(x,y,z \in X\) be points. We define a comparison triangle for the triple \((x,y,z)\) as the triangle in \(\mathbb R^2\) with vertices \(\bar x, \bar y, \bar z\), and side-lengths such that

\[\begin{align} d(x,y) &= \|\bar x - \bar y\|_2, \\ d(x,z) &= \| \bar x - \bar z\|_2, \\ d(y,z) &= \|\bar y - \bar z\|_2. \end{align}\]Note that this triangle is unique up to isometry. Denote this triangle \(\overline \Delta (x,y,z)\). The comparison angle of \(x\) and \(y\) at \(z\), denoted \(\overline \angle_z (x,y)\), is defined as the interior angle of \(\overline \Delta (x,y,z)\) at \(\bar z\).

Remark. Note that comparison triangles are sometimes called model triangles by some authors.

Informally, what we are doing here is simply taking three points in our metric space, measuring the distances between them in this space and constructing a Euclidean triangle with these distances as the side lengths. The triangle inequality within the aforementioned metric space guarantees that this will always be possible given any choice of points. Using this technique, we may compare figures in our metric space with similar figures in the plane. This idea then leads us to the main definition of this post.

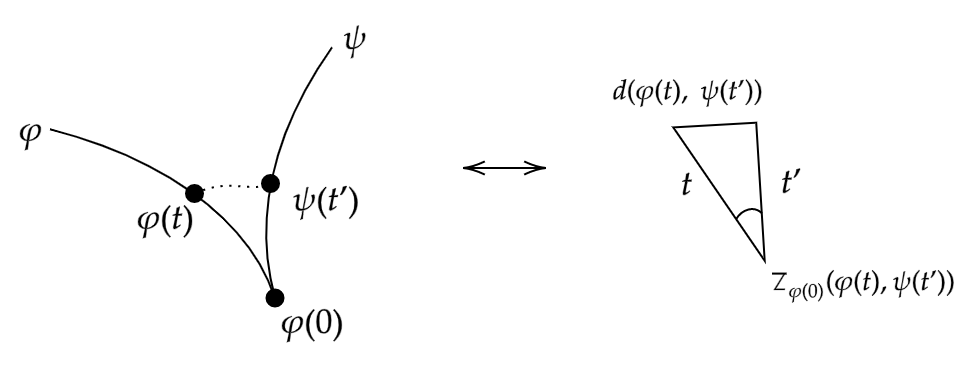

Definition 2.2. (Alexandrov angles) Let \(X\) be a metric space, and let \(\varphi : [0,r] \to X\), \(\psi : [0,s] \to X\) be geodesics such that \(\psi(0) = \varphi(0)\). The Alexandrov angle between \(\varphi\) and \(\psi\) is defined as

\[\angle(\varphi, \psi) := \lim_{\varepsilon \to 0} \sup_{0 < t,t' < \varepsilon} \overline \angle _{\varphi(0)} (\varphi(t) ,\psi(t')).\]If the limit

\[\lim_{(t,t') \to^+ (0,0)} \overline \angle _{\varphi(0)} (\varphi(t) ,\psi(t'))\]exists, we say that this angle exists in the strict sense.

Note that these angles will always exist, since \(\overline \angle _{\varphi(0)} (\varphi(t) ,\psi(t'))\) must lie in \([0,\pi]\) and thus the supremum is necessarily finite (and decreasing as \(\varepsilon \to 0\)). However they certainly need not exist in the strict sense, and we shall see some important examples of this shortly.

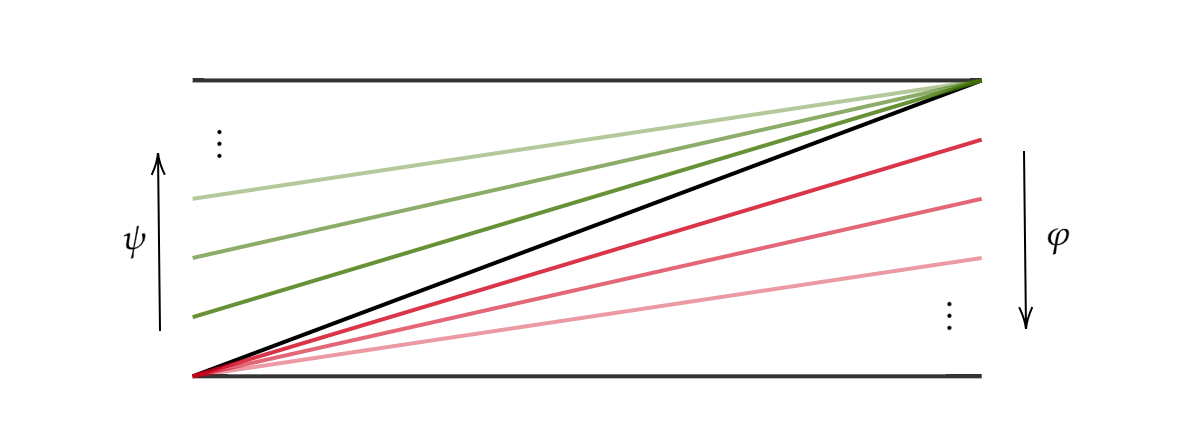

Intuitively, one can imagine that we choose two points - one on each geodesic, and consider the comparison triangle of these points and the issue point. We then slide these two points towards the issue point and see how the comparison angle changes.

As our points approach the issue point, we will see this comparison angle approach some value.

Of course this limit itself need not exist. One reason for this may be because the comparison angle may approach different values depending on whether \(t\) and \(t'\) approach \(0\) at different speeds. We will shortly see an example where this is the case.

Finally, note that this definition extends immediately to geodesic rays issuing from the same point. Essentially, the fact that our geodesic segments are of finite length plays no part in the above definition, as we only care about the behaviour of our geodesic as we approach the initial point. This idea is formalised by the germ of a geodesic (ray), but this formalism isn’t needed here.

3. Properties and Examples

We may wish to check that this definition of an angle falls in line with some of our basic intuition. For example, it should be clear that the angle between any geodesic and itself is \(0\). A similar question we might ask relates to the Euclidean idea that “straight angles” are \(\pi\) radians. We formalise this idea as follows.

Proposition 3.1. Let \(X\) be a metric space, and let \(\varphi : [a,b] \to X\) be a geodesic, such that \(a < 0 < b\). Define \(\rho_1 : [0,-a] \to X\) and \(\rho_2 : [0,b] \to X\) by

\[\rho_1(i) = -i, \ \rho_2(j) = j,\]then \(\angle (\rho_1, \rho_2) = \pi\).

The proof of this is relatively straightforward and a good exercise to get to grips with the definition. Another interesting property worth checking is that in Euclidean space, we can define a psuedo-metric (a metric that is not necessarily positive-definite) on the set of geodesics originating out of a point by measuring the angle between them. In particular, angles about a point in Euclidean space satisfy a triangle inequality. We will now show that Alexandrov angles also satisfy this same property.

Proposition 3.2. Let \(c\), \(c'\), and \(c''\) be geodesics issuing from the same point \(p\). Then

\[\angle(c', c'') \leq \angle(c', c) + \angle(c, c'').\]Proof. We will proceed by contradiction, and suppose that for some geodesics \(c\), \(c'\), and \(c''\) issuing from the same point \(p\in X\) such that \(\angle(c', c'') > \angle(c', c) + \angle(c, c'').\) Choose \(\delta > 0\) be such that

\[\angle(c', c'') > \angle(c', c) + \angle(c, c'') + 3\delta.\]By studying the \(\limsup\) in Definition 2.2, we can easily deduce that there must exist some \(\varepsilon > 0\) such that the following hold.

-

For all \(0 < t, t' < \varepsilon\), \(\overline \angle _p (c(t), c'(t')) < \angle (c,c') + \delta\),

-

For all \(0 < t, t'' < \varepsilon\), \(\overline \angle _p (c(t), c''(t'')) < \angle (c,c'') + \delta\),

-

There exists \(0 < t', t'' < \varepsilon\) such that \(\overline \angle _p (c'(t'), c''(t'')) > \angle (c',c'') - \delta\).

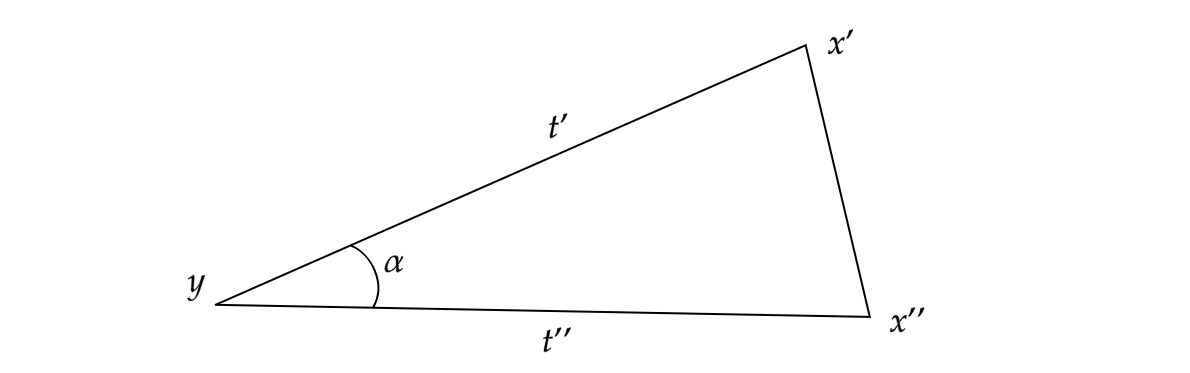

We now fix \(t'\) and \(t''\) such that (3) holds. Choose \(\alpha\) such that

\[\overline \angle _p (c'(t'), c''(t'')) > \alpha > \angle (c',c'') - \delta.\]Consider a triangle in \(\mathbb R^2\) with vertices \(x'\), \(x''\), and \(y\), such that \(\|x'-y\|_2 = t'\), \(\|x''-y\|_2 = t''\) and the interior angle between the segments \([y,x']\) and \([y,x'']\) is \(\alpha\).

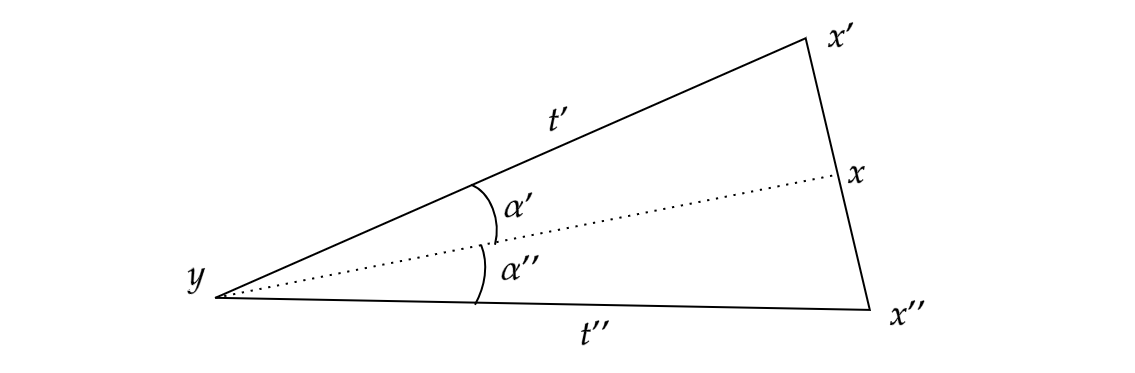

It is easily checked that \(\alpha \in (0,\pi)\), so we can safely assume that this triangle is non-degenerate (i.e. has non-zero area). From the definition of \(\alpha\), we can immediately infer that \(\|x'-x''\|_2 < d(c'(t'), c''(t''))\) by simply comparing our comparison triangle to the above. We can also infer \(\angle (c,c') + \angle (c,c'') + 2 \delta < \alpha\) from the lower bound of \(\alpha\). Using the latter of these two facts, choose \(x\) on the segment \([x',x'']\) such that the interior angle \(\alpha'\) between \([x,y]\) and \([x',y]\) is strictly greater than \(\angle(c,c') + \delta\), and similarly that the interior angle \(\alpha''\) between \([x,y]\) and \([x'',y]\) is strictly greater than \(\angle(c,c'') + \delta\).

Let \(t = \|x-y\|_2\). By inspection we can deduce that \(t \leq \max\{t',t''\} < \varepsilon\). Thus we can apply (1) and deduce that

\[\overline \angle _p (c(t), c'(t')) < \angle (c,c') + \delta < \alpha'.\]By simply inspection this reveals that \(d(c(t),c'(t')) < \|x-x'\|_2\). Similarly, we may apply (2) and deduce that \(d(c(t),c''(t'')) < \|x-x''\|_2\). To finish, we may compute

\[\begin{align} d(c'(t'), c''(t'')) &> \|x'-x''\|_2 \\ &= \|x-x'\|_2 + \|x-x''\|_2 \\ &> d(c(t), c'(t')) + d(c(t), c''(t'')). \end{align}\]As this contradicts the triangle inequality in \(X\), our result follows. //

Remark. One might ask why we choose to take the \(\limsup\) over the \(\liminf\) for the cases where the angle doesn’t strictly exist. Part of the reason is that if we define our angles using the \(\liminf\), the previous proposition does not necessarily hold. I encourage the interested reader with some spare time to see if they can find an example where the proposition fails under the \(\liminf\) definition.

So we know that \(\angle\) defines a pseudo-metric on geodesics about some point \(x\). It is easy to see that this cannot be positive-definite, as one can imagine two distinct geodesics which are identical within some neighbourhood of $x$ and thus have an interior angle of \(0\). In fact there exist examples of pairs of geodesics, whose only common point is the shared initial point, which have an Alexandrov angle of \(0\).

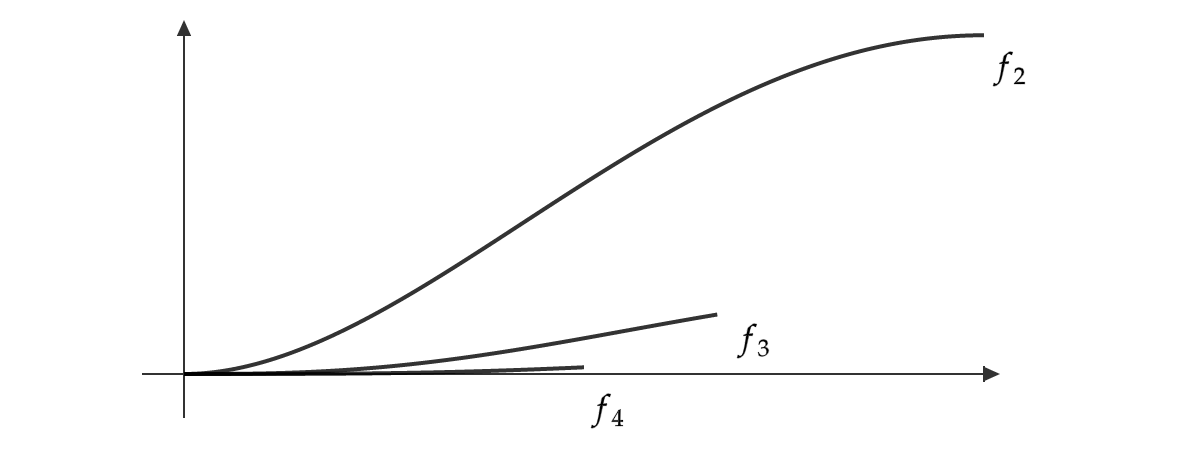

Example 3.3. Consider \(\mathbb R^2\) with the infinity-norm \(\| \cdot \|_\infty\). For every \(n \geq 2\), we define a geodesic \(f_n : [0,\frac 1 n] \to \mathbb R^2\) by \(f_n (x) = (x, [x(1-x)]^n).\) It is an easy exercise to check that each \(f_n\) is indeed a geodesic in \((\mathbb R^2, \| \cdot \|_\infty)\). Moreover, apart from the shared initial point these geodesics are pairwise disjoint. One can then use the fact that \(x \mapsto [x(1-x)]^n\) is a smooth function on \([0,1]\) with a \(0\) derivative at \(x = 0\) to argue that as these geodesics become arbitrarily “similar” as we approach the origin.

I leave the formal details to the reader but what follows is that we have an infinite number of pairwise disjoint geodesics issuing from origin, and the angle between any two is precisely \(0\).

We finish this section with a final example which demonstrates an example when these angles may not strictly exist.

Example 3.4. Let \(X = C[0,1]\) be the space of continuous functions \([0,1] \to \mathbb R\), equipped with the supremum metric

\[\rho(f,g) := \sup _{x \in [0,1]} |f(x) - g(x)|.\]Consider the geodesics \(\varphi, \psi : [0,1] \to X\) defined by the formulae

\[\begin{align} \varphi(t)(x) &= (1-t)x \\ \psi(t)(x) &= (1-t)x + t. \end{align}\]These geodesics issue from the same point in \(X\), namely the identity function. \(\varphi\) is a path from the identity function to the constant function \(x \mapsto 0\), and Similarly \(\psi\) defines a path to the constant function \(x \mapsto 1\).

One can quickly check these are indeed geodesics in \(X\) by using the supremum metric to compute \(\rho(\varphi(t),\varphi(t'))\), and similarly for \(\psi\). If we fix \(t,t' \in (0,1]\), we can compute that

\[\rho(\varphi(t), \psi(t')) = \max \{t,t'\}.\]Thus, our comparison triangle at this point have side-lengths \(t\), \(t'\), and \(\max \{t,t'\}\). The comparison angle at \(\varphi(0)\) does not then approach any single value. Indeed, we can imagine that if \(t = t'\) then this comparison angle shall be \(\frac \pi 3\) as the triangle we have is equilateral. However, if for example \(t\) is much bigger than \(t'\), then this triangle becomes a “tall” isosceles, and our comparison angle approaches \(\frac \pi 2\). Thus, we arrive at an interesting situation where our Alexandrov angle does not strictly exist. Indeed all that matters here is the ratio between \(t\) and \(t'\). If we fix this ratio as we approach \(0\), we can make our comparison angle approach any value in \([\frac \pi 3, \frac \pi 2)\). Thus, in taking the \(\limsup\) we see that the true Alexnadrov angle between these two geodesics is \(\frac \pi 2\).

4. Application: Characterising Inner Product Spaces.

Recall that we say that a norm \(\| \cdot \|\) on a vector space \(X\) arises from an inner product if there exists some inner product \(\langle \cdot , \cdot \rangle\) such that \(\| v \| = \sqrt {\langle v , v \rangle}\) for all \(v \in X\). A norm which satisfies this condition can be seen as better behaved in terms of the geometry it induces. Indeed, an important result in linear algebra and functional analysis captures this by stating that a norm arises from an inner product if and only if that norm satisfies the parallelogram law. Formally, we have the following.

Proposition 4.1. Let \((X, \| \cdot \|)\) be a normed vector space. The norm \(\| \cdot \|\) arises from an inner product if and only if

\[\| v + u \|^2 + \| v - u \|^2 = 2\| v \|^2 + 2\| u \|^2\]for all \(v,u \in X\).

Alexandrov angles provide another alternative way to capture this idea of “well-behaved geometry”. As we will shortly prove, a normed space is an inner product space if and only if all Alexandrov angles about the origin strictly exist.

Before we can prove this result, we need to build up an understanding of geodesics within normed inner product spaces. First, we will show that normed vector spaces are geodesic, and that inner product spaces are uniquely geodesic.

Proposition 4.2. Every normed vector space is geodesic, and every inner product space is uniquely geodesic.

Proof. Let \(X\) be a normed space, and let \(v,u \in X\) be vectors. Let \(d := \| v- u\|\), and define \(\psi : [0,d] \to X\) by

\[\psi(t) = (1-\tfrac t d)v + \tfrac t d u.\]A quick calculation confirms that \(\psi\) is indeed a geodesic. Denote the above geodesic \([v,u]\).

We suppose that \(X\) is an inner product space so by the previous paragraph it is geodesic. Some thought reveals that showing \(X\) is uniquely geodesic is equivalent to showing that if \(x,y,z \in X\) satisfy

\[\|x-z\| = \|x-y\| + \|y-z\|,\]then \(y \in [x,z]\). It is then easily checked that this condition is implied by (and is in fact equivalent to) the condition that for all linearly independent \(v,u \in X\), we have that

\[\| u + v \| < \|u \| + \| v \|.\]We will show that inner product spaces satisfy this second condition. Let \(u,v \in X\) be linearly independent, so by the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality we have

\[|\langle u, v \rangle | < \|u\| \|v\|.\]We then compute

\[\begin{align} \| u + v \| &= \sqrt{\langle u+v, u+v \rangle} \\ &= \sqrt{\|v\|^2 +2 \langle u, v \rangle + \|u\|^2} \\ &< \sqrt{\|v\|^2 +2 \| u \| \| v \| + \|u\|^2} \\ &= \sqrt{(\| u \| + \| v \|)^2} \\ &= \| u \| + \| v \|. \end{align}\]It follows that all inner-product spaces are uniquely geodesic. //

With this fact in mind, we can now completely characterise inner product spaces using Alexandrov angles.

Theorem 4.3. Let \(X\) be a normed space, then \(X\) is an inner product space if and only if for all geodesics rays \(\varphi, \psi : [0,\infty) \to X\) issuing from \(0\), the Alexandrov angle \(\angle(\varphi, \psi)\) strictly exists.

Proof. We first show the ‘only if’ direction, so suppose that \(X\) is an inner product space and let \(\varphi, \psi\) be two geodesics as above. By Proposition 4.2, we know that \(\varphi, \psi\) are of the form

\[\varphi(t) = tu, \ \ \psi(t) = tv,\]for some unit vectors \(u\), \(v\).

Subspaces of \(X\) isometrically embed into \(X\), so let \(Y = \textrm{span}\{u, v\}\). Since Alexandrov angles are clearly a geometric property (invariant under isometry), we now need only show that \(\angle(\varphi, \psi)\) strictly exists in \(Y\). However, it is a well-known fact from linear algebra that all \(n\)-dimensional real vector spaces are isometric to \(\mathbb R^n\). Since that this angle clearly strictly exists in \(\mathbb R^2\), we are done.

Conversely, suppose that for all geodesics rays \(\varphi, \psi : [0,\infty) \to X\) issuing from \(0\), the Alexandrov angle \(\angle(\varphi, \psi)\) strictly exists. We will show that \(X\) satisfies the parallelogram law.

We choose two linearly independent unit vectors \(u,v \in X\), and consider the geodesic rays \(\varphi\), \(\psi\) defined by \(\varphi(t) = tu\), \(\psi(t) = tv\). Let \(\alpha = \angle (\varphi, \psi)\). We claim that for all \(t,t' > 0\), we have that

\[\alpha = \overline \angle_0 (\varphi(t), \psi(t')),\]i.e. that the comparison angle remains constant as \(t\) and \(t'\) approach \(0\). To see this, fix \(t, t' > 0\), then since the angle strictly exists we can say that

\[\alpha = \lim _{s \to 0} \overline \angle_0 (\varphi(st), \psi(st')).\]Applying the fact that \(\cos\) is a continuous function on \(\mathbb R\), as well as the law of cosines, we deduce

\[\begin{align} \alpha &= \lim _{s \to 0} \overline \angle_0 (\varphi(st), \psi(st')) \\ &= \lim _{s \to 0} \frac 1 {2s^2 t t'} (s^2t^2 + s^2 t'^2 - \| stu - st'v \|^2)\\ &= \lim _{s \to 0} \frac 1 {2t t'} (t^2 + t'^2 - \| tu - t'v \|^2)\\ &= \frac 1 {2t t'} (t^2 + t'^2 - \| tu - t'v \|^2)\\ &= \overline \angle_0 (\varphi(t), \psi(t')). \end{align}\]Thus our claim follows. We now have everything we need to show that the parallelogram law holds. We need only consider the linearly independent case, as the linearly dependent case is trivial. So let \(v\) and \(u\) be linearly independent vectors, and apply the previous claim to the unit vectors \(\frac v {\| v \|}\) and \(\frac {v+u} {\| v+u \|}.\) In doing so, we see that

\[\overline \angle_0 (v, v+u) = \overline \angle_0 (v, \tfrac 1 2 (v+u)).\]Applying the law of cosines to both sides of this equality, we get

\[\begin{align} &\frac 1 {2\|v\| \|v+u\|} (\|v\|^2 + \|v+u\|^2 - \|u\|^2 ) \\ &= \frac 1 {\|v\| \|v+u\|}(\|v\|^2 + \tfrac 1 4 \|v+u\|^2 - \tfrac 1 4 \|u-v\|^2 ). \end{align}\]From here it is a simple matter of rearrangement to show that the parallelogram law holds, and it follows that \(X\) is an inner product space. //

As an immediate corollary we may deduce that \(C[0,1]\) with the supremum norm is not an inner product space due to Example 3.4.

We will finish this section with a vague recollection of a faded memory - don’t inner product spaces have angles defined on them already? The answer is of course yes! Recall that the angle \(\alpha\) between two vectors \(u\) and \(v\) in an inner product space is usually defined by

\[\cos \alpha = \frac {|\langle u,v \rangle |} {\|u\| \|v\|}.\]If we associate a vector with its corresponding geodesic ray issuing from the origin, then it is not too difficult to check using the law of cosines that this definition of an angle between two vectors is in fact equivalent to the Alexandrov angle. I will however leave this as an exercise, as I found it relatively enlightening to see how the standard angle definition relates to the very geometric definition of Alexandrov angles.

5. Closing Remarks

If one is working with non-Euclidean spaces, such as hyperbolic or spherical spaces, there do exist standard “cosine laws” for these spaces which define angles in a more direct way. However, wonderfully it can be shown that these non-Euclidean cosine laws are in fact equivalent to the Alexandrov definition of an angle within their respective spaces. This post is already far too long, but a reader interested in exploring these ideas more should direct their attention to [1]. Specifically Proposition 2.9 of Chapter I.2 addresses this very question.

In fact much of this post has been adapted from parts of [1]. Thus if any reader craves a more official exposition of all discussed above, I would direct them to Chapter I.1 of the aforementioned text. This definition leads to the field of Alexandrov geometry, and the more-advanced reader who wishes to delve deeper into this area of mathematics is pointed towards [4] which provides a complete introduction to this field and its topics. Anybody looking to delve into the history of this generalisation may wish to track down the two seminal papers of this idea [2] and [3]. Do be warned however that these papers are not in English, and a brief history of the field is also presented in [4].

If anything discussed above is in need of clarification or correction, then I finally encourage the reader to point these issues out to me as soon as possible - either via the comments below or via email.

6. References

-

Bridson, M. R., & Haefliger, A. (2013). Metric spaces of non-positive curvature (Vol. 319). Springer Science & Business Media.

-

Alexandrov, A. D. (1951). A theorem on triangles in a metric space and some of its applications. Trudy Mat. Inst. Steklov., 38, 5-23.

-

Alexandrov, A. D. (1957). Uber eine Verallgemeinerung der Riemannscen Geometrie. Schriftenreiche der Institut fur Mathematik, 1, 33-84.

-

Alexander, S., Kapovitch, V., & Petrunin, A. (2019). An invitation to Alexandrov geometry: CAT (0) spaces. Springer International Publishing.