Hilbert's hotel, but the guests are mere mortals

First published July 26, 2020Tags: [

maths

combinatorics ]

We will consider a variation of Hilbert’s hotel, within which guests may not be relocated too far from their current room.

This post will be hopefully more accessible than other topics on this site, and should require no more than some basic set theory to comprehend. The contents of this post aren’t meant to be too thought provoking, as the point being made is quite moot. My aim is to demonstrate the (in my opinion) relatively nice combinatorial argument which falls out of this toy problem.

Edit, 26/7/2020: A small translation error has been corrected.

1. Introduction

Hilbert’s Paradox of the Grand Hotel is a relatively famous mathematical thought experiment. It was introduced by David Hilbert in 1924 during a lecture entitled ‘About the Infinite’ [1, p. 730] (translated from the German ‘Über das Unendliche’). Hilbert’s goal in this demonstration was to show how when dealing with infinite sets, the idea that the “the part is smaller than the whole” no longer applies. In other words, the statements “the hotel is full” and “the hotel cannot accommodate any more guests” are not necessarily equivalent if we allow an infinite number of rooms. Hilbert gives the following explanation for how one can free up a room in an infinite hotel with no vacancies.

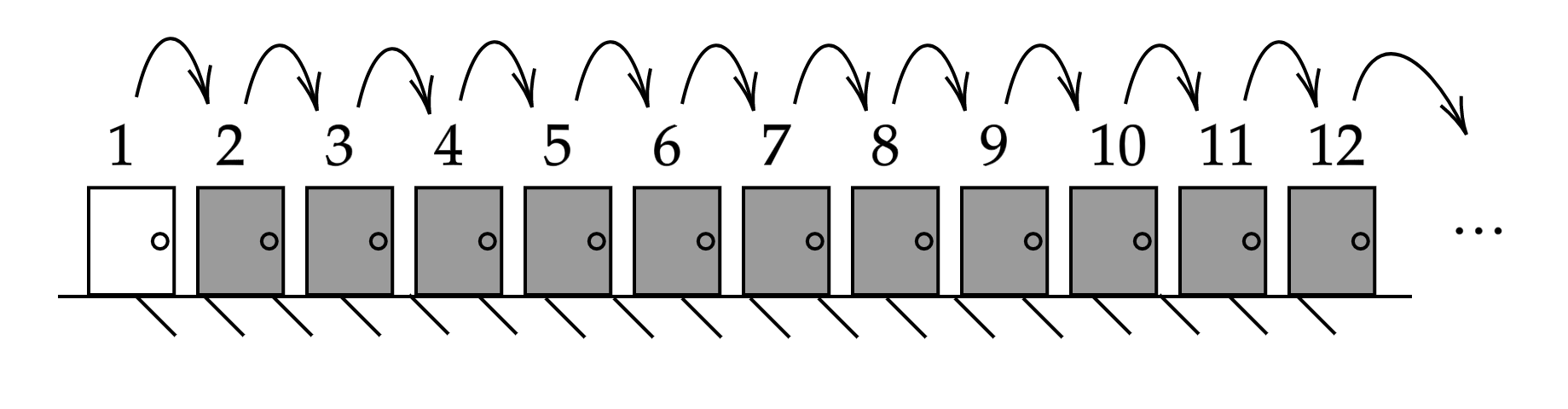

We now assume that the hotel should have an infinite number of numbered rooms 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 … in which one guest lives. As soon as a new guest arrives, the landlord only needs to arrange for each of the old guests to move into the room with the number higher by 1, and room 1 is free for the newcomer.

Indeed this can be adjusted to allow for any arbitrary number of new guests. For any natural number \(c\), we can accommodate an extra \(c\) by asking every current guest to move from their current room \(n\) to the room \(n+c\). Upon doing this, the rooms numbered 1 to \(c\) shall become available. Hilbert then goes on to demonstrate that we can extend this to even allowing an infinite number of new guests in our already full hotel.

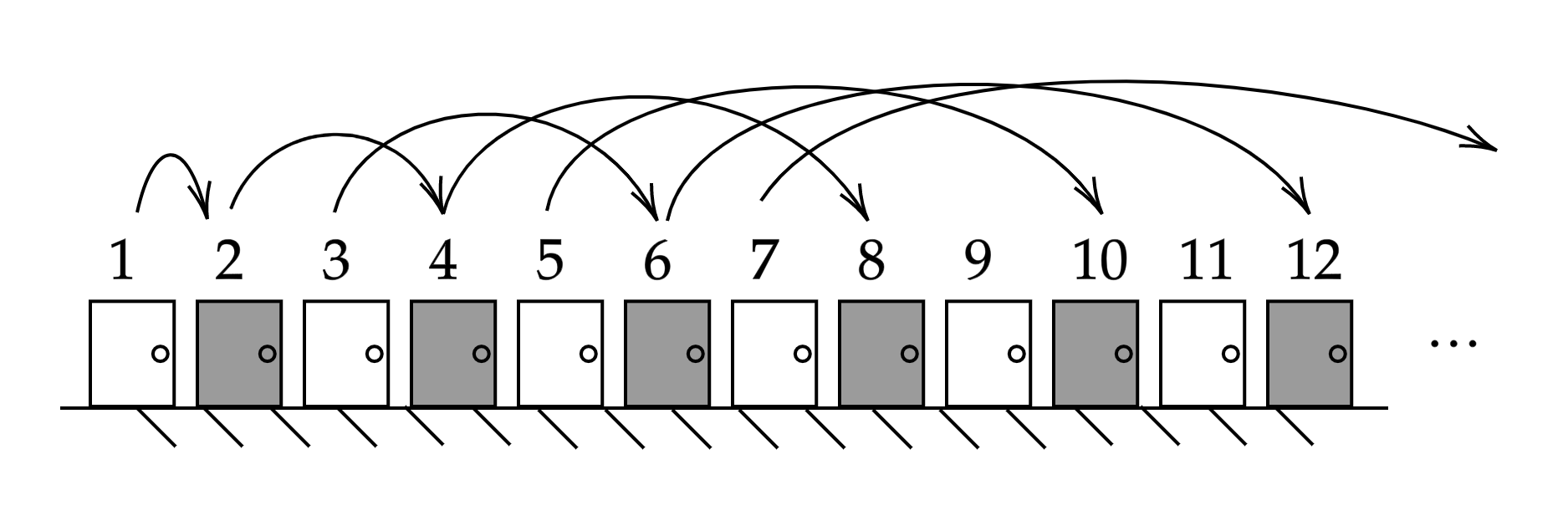

Yes, even for an infinite number of new guests, it is possible to make room. For example, have each of the old guests who originally held the room with the number \(n\), now move into the one with the number \(2n\), whereupon the infinite number of rooms with odd numbers become available for the new guests.

This fact is somewhat remarkable and can seem rather counterintuitive upon first viewing. If we imagine ourselves standing in this hotel’s fictional foyer, the image of a corridor stretching off to infinity is sure to be a daunting one, and trying to make any kind of practical considerations within this setting is surely a fool’s errand. Alas that is exactly what the rest of this post shall try to do.

Suppose that we have our own grand hotel, and every room is currently occupied by a guest with a finite lifespan. We receive word that an infinitely long coach of tourists will be arriving shortly, and are asked to accommodate as many guests as possible. To accomplish this we may move guests between rooms as in the previous case, but with the catch that our current guests must arrive at their new room before their timely demise.

To explain further, consider the two examples laid out by Hilbert above. In the first case every guest simply moves one room along, possibly only a few meters (say \(x\) meters) away from their current room. This is an easy task that hopefully every guest will be able to accomplish within their lifespan. We have freed up 1 room with no dead residents. Success. Consider the second case however, where a guest in room \(n\) will have to move along \(n \times x\) meters to the room \(2n\). As \(n\) grows to infinity, this walk will of course become arbitrarily large and all but a finite number of our guests must perish en route to their new abode. Thus, while we have made an infinite number of rooms available, we have also caused the deaths of the majority of our guests. Not ideal.

Remark. Considering the second example, if we suppose that the rooms are 1 meter apart then the guest in room \(10^{27}\) will have to cross the observable universe in order to reach their new room.

Being the kind of mathematician to own an infinite hotel, we wish to optimise our potential income here. Thus we work will answer the question “how many rooms can we make available without killing any of our guests?”. One would hope that there is some clever system which would allow us to still free up an infinite number of rooms. However as we shall shortly prove, such a method does not exist. Requiring that our guests survive their journey between rooms is just much too grand a request if we wish to increase our hotel capacity by an infinite amount.

2. The Argument

To formalise this problem, we will model it as follows. We will identify every room with its room number, and the hotel itself shall just be the set of room numbers. In particular our hotel is simply the set of natural numbers \(\mathbb N\). The movement of current guests shall be modelled by a function \(f : \mathbb N \to \mathbb N\). Of course every guest must be assigned a unique room, and so we add the requirement that \(f\) is injective. If we let

\[E_f := \mathbb N \setminus \text{Im} f\]denote the set of rooms left available after applying \(f\), we can see that our goal is to maximise the order of \(E_f\).

In adding the requirement that guests cannot walk “too far”, we are stipulating that for all \(n \in \mathbb N\), \(|f(n) - n |\) cannot grow too large. To simplify things slightly, we will assume every guest has one universal maximum walking distance, say \(c\). Thus we wish to bound

\[|f(n) - n | \leq c\]for every \(n \in \mathbb N\). We will say that a function satisfying this condition is relatively bounded by \(c\).

Remark. Note that the term ‘relatively bounded’ as it is used here is by no means standard, and is simply being defined here for convenience.

Returning to Hilbert’s examples once again, if we consider the first case where we move every guest to the next room over we can see that \(|E_f| = 1,\) and that \(|f(n) - n | = 1\) for all \(n\). In the second case, we have that \(E_f\) is countably infinite, but for every \(n\) we have that \(|f(n) - n | = n,\) which grows arbitrarily large. This breaks our imposed condition that \(f\) be relatively bounded, and so this strategy is not valid.

Clearly we can accommodate \(c\) new guests by mapping \(f(n) = n+c\) as discussed earlier. Our claim is that this is the best one can do under these mortal circumstances.

We shall model our choice of \(f\) as follows. Suppose we have a warden who walks down the corridor, knocking on each door in turn and telling the residents to which suitable room they must move. This warden has a list of all rooms, which are initially all marked as “FREE”. Upon telling somebody to move to room \(m\) the warden shall mark it as “OCCUPIED” on their list, and this room will no longer be considered for later moves. The warden also begins with an empty list of “EMPTY” rooms. If the warden is currently relocating resident \(n\) with the room \(n - c\) marked as “FREE”, and the warden does not choose this room, then they shall add \(n - c\) to their “EMPTY” list before moving on. The intuition behind this is that if room \(n - c\) is not chosen for resident \(n\) or earlier, then it will never be chosen and shall remain empty until the new guests arrive.

With this combinatorial model of \(f\), it is clear that our goal is to grow the “EMPTY” list. However, note that this list only grows in a very specific circumstance. This observation will allow us to prove our claim.

Theorem 1. The order of \(E_f\) for any injective function \(f : \mathbb N \to \mathbb N\) which is relatively bounded by \(c\) is no larger than \(c\).

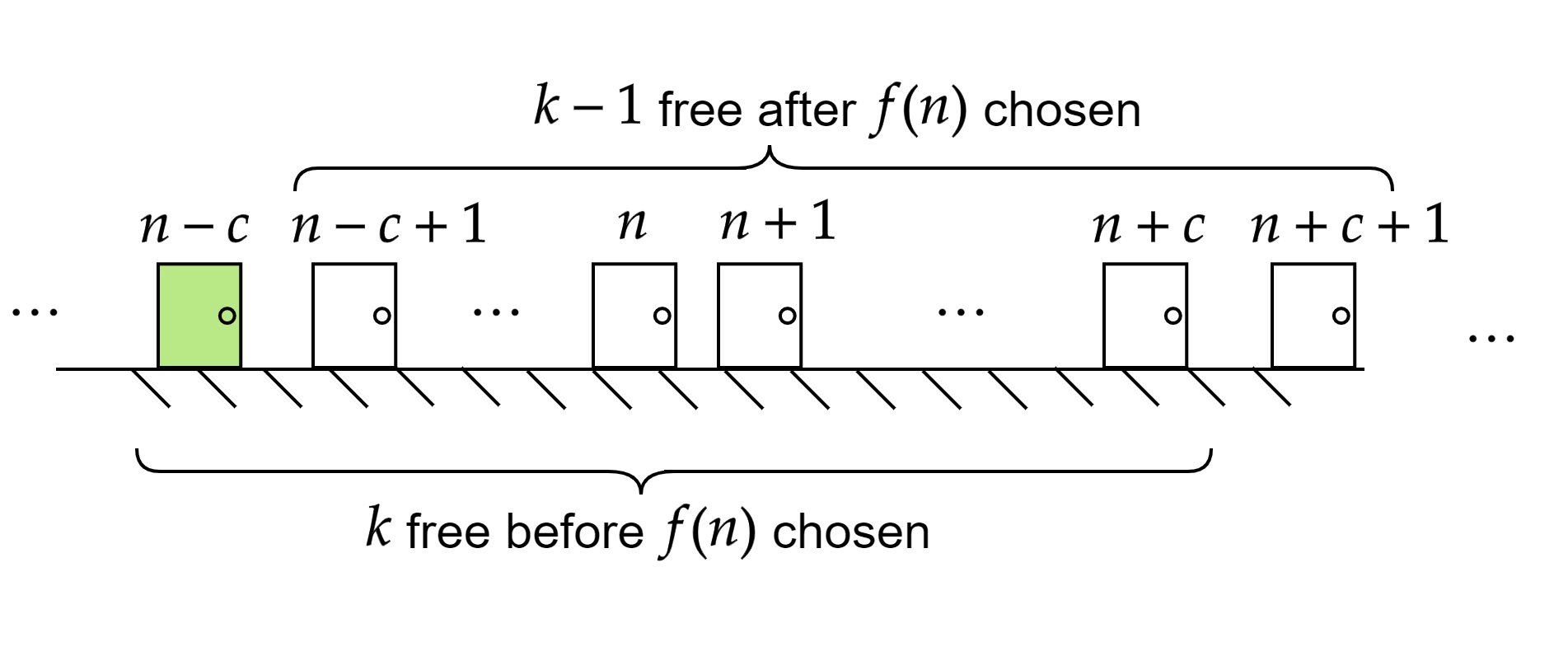

Proof. We will apply our ‘warden’ model, and proceed by induction to show a slightly stronger claim. We will show for all \(n \in \mathbb N\) that if the warden has \(l\) rooms on their “EMPTY” list, and is knocking on the door of room \(n\) with \(k\) suitable “FREE” rooms which this resident can be relocated into, then

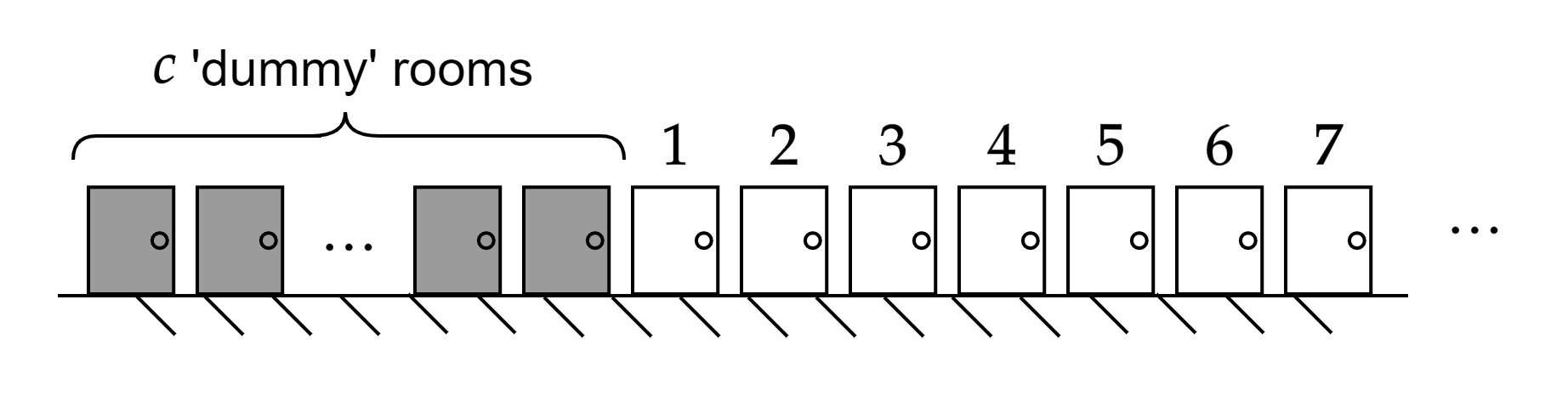

\[l + k = c+1.\]Since \(k\) is always at least 1 (room \(n+c\) is always free), our claim follows. To simplify the induction without loss of generality, we suppose that the hotel is padded with \(c\) ‘dummy’ rooms to the left of room 1, which are permanently occupied. This removes the need to treat the first few cases as somehow different because they aren’t surrounded by \(2c\) other rooms.

For the base case, suppose that the warden is knocking on the door of room 1. Currently their “EMPTY” list contains 0 rooms, and the number of rooms to which this resident can be moved to is \(c+1\). Our claim thus follows trivially.

Next, we shall perform the inductive step. Suppose the warden has \(l\) rooms on their “EMPTY” list and is knocking on the door of room \(n\) with \(k\) suitable “FREE” rooms which this resident can be relocated into, such that \(l + k = c+1\). We have two cases.

Case 1. Suppose room \(n-c\) is not currently free. Inspection reveals that every room which is “FREE” near room \(n\) is also then near room \(n+1\). However, resident \(n\) must then be allocated a room from the pool of rooms which resident \(n+1\) is choosing from next. Since resident \(n+1\) can also choose room \(n+c\) (which is guaranteed to be free), they shall be choosing from \(k - 1 + 1 = k\) rooms. The “EMPTY” list remains of length \(l\), and it follows that our claim also holds when the warden knocks on door \(n+1\).

Case 2. Suppose instead that room \(n-c\) is currently free. In this case, one can see that every “OCCUPIED” room which was in range of room \(n\) must also have been in range of room \(n+1\). We now consider two subcases.

First suppose the warden chooses \(f(n) = n-c\). Then the new room that resident \(n\) occupies will not be within range of room \(n+1\), and so it follows that resident \(n+1\) will also have \(k\) possible rooms to choose from. Since the “EMPTY” list remains at length \(l\), our claim follows.

If instead \(f(n) \neq n-c\), then this means \(n-c\) will be added to the “EMPTY” list, and the list will now be of length \(l' := l+1\). In this case, resident \(n\) shall now occupy a new room within range of \(n+1\). This will reduce the number of possible choices for \(f(n+1)\) by 1. Thus when the warden knocks on the next door, there will only be \(k' := k - 1\) suitable free rooms to choose from. We finally have that

\[k' + l' = k + l -1 + 1 = k + l = c+1\]as required.

It follows that this list of “EMPTY” rooms can only contain at most \(c\) rooms, and our theorem is proven. //

Edit, 27/7/2020: Better arguments for the above have since been demonstrated. I’d encourage the reader to try figure out a shorter proof for themselves, otherwise some of these arguments can be found in this reddit thread.

3. Some Numbers

As it turns out, if we add the restriction to Hilbert’s thought experiment that our guests are all mere mortals, then a full hotel can only accommodate a finite number \(c\) of new guests. With a goal of estimating this value \(c\), I will finish this short article with some napkin mathematics. Combining some assumptions about the guests staying at our hotel with some hastily googled statistics, I will try to pull out some concrete numbers about our hotel’s optimal performance. After all, we know that \(c\) is finite, why not try calculate it?

Suppose that we have full control over who we let stay in our hotel, in that every room contains a human perfectly optimised for relocation to the furthest room possible. I will take this as a female toddler with an age 18 months old, since females tend to live longer and most children can walk fairly confidently by this age. Countries exist with a female life expectancy of ~90 years (Monaco, for example), so we shall assume that our guests all share this lifespan of 90 years. This means we can expect the Monégasque toddlers in our hotel to live for a further 88.67 years, or 2,796,300,000 seconds.

The average walking speed of a human being is 1.4 meters per second. Let us assume that the distance between rooms is about 3 meters (this is not a luxury hotel). Calculation then tells us that it would take a person on average 2.14 seconds to travel from one room to the room next door. Putting these numbers together, we see that during the rest of their lifespan, our guests can walk up to 1,306,682,243 rooms away. By Theorem 1, it thus follows that this hotel could only accommodate 1,306,682,243 new guests before existing guests began to die on their journeys.

I believe this provides a relatively sound upper bound to how many new guests Hilbert could actually accommodate. Indeed 1,306,682,243 is less than infinity, and in fact is actually less than the population of India. If anybody dreaming of becoming a transfinite architect is reading this, don’t let this reality check demotivate you. Follow your dreams.

4. References

- Hallett, M., Majer, U. and Schlimm, D., 2013. David Hilbert’s Lectures on the Foundations of Arithmetic and Logic 1917-1933 (Vol. 3). Springer-Verlag.