An upper bound on Ramsey numbers (revision season)

First published May 02, 2019Tags: [

combinatorics

ramsey-theory

ramsey-numbers

maths

revision ]

I will present a short argument on an upper bound for \( r(s) \), the Ramsey Number associated with the natural number \(s\).

The reader need only know some basic graph theory but any familiarity with Ramsey theory may help the reader appreciate the result more.

1. Preliminaries

Definition 1. (Ramsey Numbers) The Ramsey Number associated with the natural number \(s\), denoted \(r(s)\), is the least such \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that whenever the edges of the complete graph on \(n\) vertices (denoted \(K_n\)) are coloured with two colours, there must exists a monochromatic \(K_s\) as a subgraph.

Definition 2. (Off-diagonal Ramsey Numbers) Let \(r(s,t)\) be the least \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that whenever the edges of \(K_n\) are 2-coloured (say, red and blue), we have that there must exist either a red \(K_s\) or a blue \(K_t\) as a subgraph.

Some immediate properties that follow from the definitions are that for all \(s,t \in \mathbb{N}\), we have

\[r(s,s) = r(s), \\ r(s,2) = s,\]and

\[r(s,t) = r(t,s).\]If you’re struggling to see why the second one is true, recall that the complete graph on 2 vertices is just a single edge. One may question whether these numbers necessarily exist. This is known as Ramsey’s theorem, which I will now state conveniently without proof.

Theorem 1. (Ramsey’s Theorem) \(r(s,t)\) exists for all \(s,t \geq 2\), and we have that

\[r(s,t) \leq r(s-1,t) + r(s,t-1)\]for all \(s,t \geq 3\).

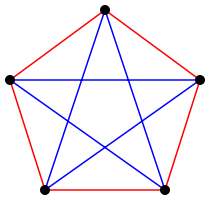

To help illustrate what we are talking about, consider this colouring of the complete graph on 5 vertices.

Inspection reveals that there is no completely red (or blue) triangle, which in fact constitutes a proof by counter example that \(r(3) > 5\). In fact, it can be shown that \(r(3) = 6\), that is, there does not exist a 2-colouring of \(K_6\) that contains no monochromatic triangles.

2. An Upper Bound

Ramsey Numbers are notoriously difficult to calculate exactly - it is almost exclusively done by proving tighter and tighter bounds on them until we have equality of some description. I will prove one of these aforementioned bounds.

Lemma 2. We have that for any \(s,t \geq 2\),

\[r(s,t) \leq { {s+t-2}\choose{s-1} }.\]Proof. This result is shown by induction on \(s+t\) using the inequality in Theorem 1. As a base case, suppose that either \(s\) or \(t\) equals \(2\). Without loss of generality, due to the symmetric nature of \(r(s,t)\), suppose \(s = 2\). We have that

\[r(2,t) = t = { {t}\choose{1} } = { {s + t - 2}\choose{s-1} }\]and we are done. Now suppose that \(s,t \geq 3 \). Then by Theorem 1 and Pascal’s identity, we have

\[\begin{align} r(s,t) & \leq r(s-1,t) + r(s,t-1) \\ & \leq { {s + t - 3}\choose{s-2} } + { {s + t - 3}\choose{s-1} } \\ & = { {s + t - 2}\choose{s-1} } \end{align}\]And the induction is complete. //

Next we shall prove an inequality regarding the binomial coefficient itself.

Lemma 3. For any \(m \in \mathbb{N}\), we have that

\[{ {2m}\choose{m} } < \frac{2^{2m}}{\sqrt{2m+1}}.\]Proof. We proceed by induction. When \(m=1\) we have that

\[{ {2}\choose{1} } = 2 < \frac{4}{\sqrt{3}}.\]Let \(m \geq 1\). We have

\[\begin{align} \frac{1}{2^{2(m+1)}} { {2(m+1)}\choose{m+1} } & = \frac{(2m+2)!}{2^{2m+2}((m+1)!)^2} \\ & = \frac{(2m)!(2m+1)(2m+2)}{2^{2m} (m!)^2 (m+1)^2} \\ & = \frac{(2m)!}{2^{2m} (m!)^2}\frac{2m+1}{2m+2} \\ & < \frac{1}{\sqrt{2m+1}} \frac{2m+1}{2m+2} \\ & = \frac{\sqrt{2m+1}}{2m+2}. \end{align}\]It remains to be shown that \( \frac{\sqrt{2m+1}}{2m+2} \leq \frac{1}{\sqrt{2m+3}} \). We do this by considering squares of both sides. Observe that

\[(\sqrt{2m+1} \sqrt{2m+3})^2 = 4m^2 + 8m + 3 < 4m^2 + 8m + 4 = (2m+2)^2\]and from this our result follows. //

We now tie these Lemmas together to give our main result.

Theorem 4. For any \(s\geq 2\), we have that

\[r(s) \leq \frac{4^s}{\sqrt{s}}.\]Proof. In this proof we use a slightly weaker version of Lemma 3, namely that

\[{ {2m}\choose{m} } \leq \frac{2^{2m}}{\sqrt{2m}}.\]First, we simply recall that \(r(s) = r(s,s)\), so by Lemma 2 we have

\[r(s) \leq { {2s-2}\choose{s-1} }.\]Next, using (the slightly weakened) Lemma 3 and some algebra we see

\[\begin{align} { {2s-2}\choose{s-1} } & \leq \frac{2^{2s-2}}{\sqrt{2s-2}} \\ & = \frac{4^s 2^{-2}}{\sqrt{2s-2}} \\ & \leq \frac{4^s}{\sqrt{2} \sqrt{s-1}}. \end{align}\]It remains to be shown that \(\sqrt{2} \sqrt{s-1} \geq \sqrt{s}\). Observe that for \(s\geq 2\)

\[\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}} \leq \sqrt{1-\frac{1}{s}} = \sqrt{\frac{s-1}{s}}\]from which our result follows.//

3. Closing Remarks

This problem was found in a problem sheet from my Combinatorics course, and I wrote this up as a short mathematical writing exercise and for a revision break. I plan to write up more posts on interesting questions posed in problem sheets or elsewhere as a way to keep me sane in the next month or so. (Edit, 6/6/19: I did not manage to write about anything else.)

It is interesting to note that proving the stronger version of Lemma 3 presented ended up being much easier than showing the weaker version used in Theorem 4. A big thanks to the people on the Mathematics Stack Exchange who helped me out with this problem and in particular Lemma 3. See the question and answers here.